A Brief History of Cahokia Mounds

by

John J. Dunphy

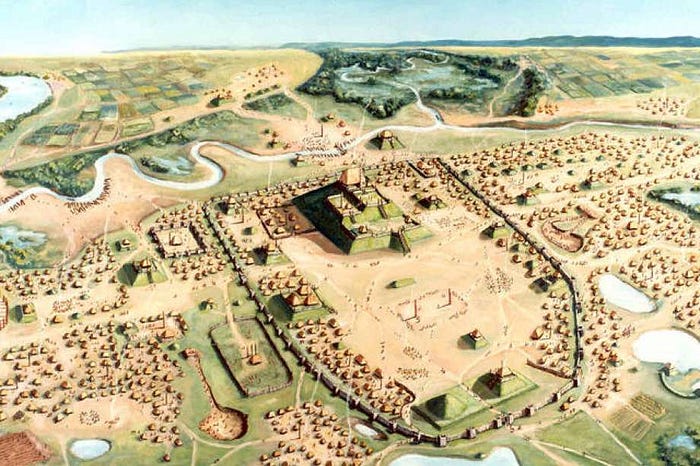

One can view St. Louis’s Gateway Arch from any number of point in the Metro East. Many regard the best viewing spot as atop Monk’s Mound, a magnificent earthen structure that was built by Native Americans near present-day Collinsville. Monk’s Mound, which is 1,037 feet long and 790 feet wide, is actually larger at its base than the Great Pyramid of Giza. It is the centerpiece of the prehistoric site known as Cahokia Mounds.

The civilization-builders who once lived at this site did not refer to the area as Cahokia or Cahokia Mounds. The name that these Indians called themselves is lost to history. Archaeologists refer to this particular Native American culture as the Mississippian.

Scholars remain divided concerning the genesis of the Mississippians. Some maintain that these Native Americans migrated to the area’s great flood plain, while others contend that the Mississippians were the successors to earlier cultures. We can be certain, however, that a variety of geographical factors combined to facilitate the rise of the Mississippians around 1000 A.D. The Mississippi, Missouri and Illinois Rivers created the American Bottoms, a nutrient-rich flood plain that stretches 70 miles along the Father of Waters from present-day Alton to Chester. Maize and other crops thrived in its soil. Fish, migratory waterfowl and white-tailed deer also provided food for these Indians.

The Mississippians engaged in trade with other Native American cultures, traveling vast distances along routes pioneered by earlier inhabitants, such as the Woodland Indians. The three great rivers provided natural avenues of commerce for canoes and allowed the Mississippians to reach the Upper Great Lakes, where they acquired copper, and the Gulf of Mexico, their source for seashells. Land trading routes included journeys into the southern Appalachian region with its deposits of mica. Archaeologists have found Mississippian-style pottery throughout the southeastern United States and as far north as Red Wing, Minnesota.

But does geography alone account for the rise of Cahokia? Perhaps not.

Archaeologist Timothy Pauketat in 1993 proposed a theory he called “the Big Bang,” which argued that Cahokia’s population exploded in the early eleventh century. In a span perhaps as brief as ten years, a village numbering approximately 1,000 residents expanded into a city of about 10,000. Inhabitants of the region had been growing maize for at least 200 years, so Cahokia’s dramatic growth can’t be attributed to the sudden introduction of this staple crop. Nor can the city’s role as an early American trading hub fully account for its success. What, then, is the answer?

Pauketat believes that a supernova recorded in 1054 might have inspired sudden growth of this city. He and Cahokia expert Thomas E. Emerson also note that the Zulu empire that rose and fell in southeastern Africa in the nineteenth century was forged by a single man — Shaka Zulu. They believe that the rise of a charismatic leader could well explain the flowering of Mississippian culture. The evidence for this theory surfaced in 1967, when archaeologist Melvin Fowler excavated Mound 72.

A ridge-shaped earthen structure located 1,000 yards north from the massive Monk’s Mound, Mound 72 was less than six feet high. Its grim contents, however, were anything but inauspicious.

Mound 72 contained three smaller burial mounds that held about 260 human skeletons. One skeleton was that of a man who was obviously a great leader. Archaeologists estimate that he died in his forties, an advanced age for a Mississippian. He had been placed on a bed of more than 20,000 rare white sea shells that had been shaped to resemble a falcon. The falcon’s head was beneath the leader’s head, while its wings and tail were beneath his arms and legs.

And he was not buried alone.

In a trench near this great leader, fifty-four young women were laid out in two rows. Their pelvic areas indicated that they had not borne children and, therefore, were possibly virgins. Mound 72 also held some skeletons that were missing their hands and heads, indicating human sacrifice. Some of the finger bones of other skeletons were pressed into the soil, bearing mute testimony that they had been buried alive.

In addition to these sacrificial victims, the Mississippians buried items of great value with their revered leader. Archaeologists found sheets of rolled copper, arrowheads, mica and chunky stones in mound 72.

Human sacrifice was a grim reality of life at Cahokia. Young women were ritually killed and buried on rows of white pelts or another kind of special lining. Some of these victims were fed a diet that was high in corn during the final year of their lives. Pauketat believes that they were meant to personify a corn goddess and were sacrificed to ensure a bountiful harvest.

While Fowler and his team was excavating mound 72, archaeologist Charles Bareis was uncovering a refuse pit located just a short distance from the leader’s burial site. The pit, as long as a football field and about 60 feet wide, contained the remains of many feasts which, considering the ripe berries, must have taken place in autumn. Bareis and his team were surprised to find the broken remains of religious objects previously unseen at Cahokia Mounds. Native American craftsmen had painstakingly fashioned arrowheads and human figures from quartz crystals. The refuse pit also held broken pottery, brightly-painted and sometimes inscribed with wings, eyes and strange faces that archaeologists believe might have represented ceremonial masks.

The refuse pit was closed about 1050 A.D., a date which archaeologists believe approximately coincides with the death and burial of this chief. Was he indeed the charismatic leader who was responsible for the rise of Cahokia as a great metropolis. Did the feasts cease with his death?

Archaeologists believe that the leader of the Mississippian community at Cahokia Mounds lived in a massive building atop Monk’s Mound. The building measured 105 feet long, 48 feet wide and 50 feet high — an imposing structure indeed! Still, it almost pales into insignificance when compared to the mighty mound upon which it rested.

Monk’s Mound rises in four terraces to a height of 100 feet. The Mississippians constructed it over a period of three hundred years by painstakingly scooping up basket after basket of dirt — some 19 million cubic feet of the stuff, according to archaeologists — and then carrying the baskets to the mound site. It is believed that each basket held about 55 pounds of dirt, which means that it took around 14.6 million loads to build Monk’s Mound.

Archaeologists note that it would take approximately 229,166 pick-up truck loads to transport 19 million cubic feet of soil — and this culture possessed no machinery whatsoever. The Mississippians didn’t even have horses to assist them in this backbreaking task.

Archaeologists in 1971 discovered an artifact on Monk’s Mound that underscored the Mississippians’ capacity for symbolic expression. The “Birdman Tablet” contains a depiction of a masked man with a bird’s beak, feathers and earspools. The reverse of the tablet is adorned with a snakeskin pattern. The man represents the earth world of humans, while the bird’s beak and feathers symbolize the sky. The snakeskin personifies the underworld, thereby completing the three-world symbolism of the tablet. The Birdman image is now the official logo of Cahokia Mounds.

Monk’s Mound is a staggering achievement. But it is far from being the only marvel of prehistoric engineering at Cahokia Mounds.

Dr. Warren Wittry had been studying excavation maps of the area in 1961 when he observed a series of oval-shaped pits. He concluded that these pits had once held a circle of red cedar posts, with a sunrise arc that functioned as a calendar to mark the changing of the seasons. The other posts of the sunrise arc might have identified important agricultural festivals, while non-sunrise arc posts could have aligned with stars and planets.

Further investigation revealed there to have been no less than five Woodhenge circles, all built in the same location during the period 900 A.D. to 1100 A.D. The first circle had consisted of 24 cedar posts, while the second circle had numbered 36. The third circle, thought to have been raised about 1000 A.D., had been comprised of about 48 such posts. A fourth circle had consisted of 60 posts, and an incomplete fifth circle held only 13 posts in the sunrise arc. Archaeologists postulate that this fifth Woodhenge, which would have required 72 posts to form a complete circle, had been left unfinished for the entirely mundane reason that red cedar trees were becoming scarce.

Wittry discovered a beaker fragment near the winter solstice post of Woodhenge. The beaker is inscribed with a cross that Wittry believes represents the world. The cross is inside a circle with two paths — one open and the other closed. Wittry postulates that the open path leading to the circle represents the rising sun at the winter solstice, while the closed path symbolizes that day’s setting sun.

Archaeologists reconstructed the third Woodhenge circle in 1985 to give visitors a better appreciation for the extraordinary civilization that once flourished at Cahokia Mounds. The winter and summer solstices, as well as the vernal and autumn equinoxes, are popular days to visit Woodhenge. Visitors arrive before dawn to watch the sun rise behind the winter and summer solstice posts and the single equinox post.

A vernal or autumn equinox at Woodhenge is particularly spectacular. The equinox post aligns with Monk’s Mound to the east so that, at dawn on the first day of spring and fall, it looks as though Monk’s Mound is giving birth to the sun. Since the Mississippian ruler lived in a building atop Monk’s Mound, the community’s inhabitants might have been led to believe that their chief enjoyed a special relationship with the heavenly body.

During several of my visits to Woodhenge, a visitor struck a hand-held drum, one beat every five seconds, while the sun rose behind the equinox or solstice post. It might almost have been a heartbeat — the slow, fragile heartbeat of the new season whose birth this sunrise marked.

By 1150 A.D., the Mississippian community at Cahokia Mounds had a population of about 20,000, making it larger than London. While Europe was locked in the Dark Ages, a remarkable civilization flourished at Cahokia Mounds. Until 1800, no city in the United States was as large as the Cahokia Mounds of centuries past. By 1400, however, the site was abandoned.

Archaeologists remain uncertain why this extraordinary civilization ultimately declined and vanished. A major climate change occurred about 1250 A.D., with colder temperatures leading to a shorter growing season. Perhaps crops became insufficient to support such a large population. Overhunting could have depleted the area’s animals, which would have caused a further food shortage.

The problem of garbage and human waste disposal could have posed a problem for the Mississippians. A polluted water supply would have led to disease, which might have spread rapidly through such a large population.

Yet another possibility is conflict with other Native American cultures. Archaeologists have discovered that a two-mile long stockade surrounded the central portion of Cahokia. They estimate that the Mississippians started construction of this stockade around 1100 A.D., and then rebuilt it three times over a period of 200 years. Each construction of the stockade required 15,000 to 20,000 oak and hickory logs that were one foot in diameter and twenty feet high. We can only speculate as to the stockade’s purpose, although it could well have been erected to protect the community from hostile invaders.

In any event, the Cahokia Mounds region remained uninhabited until about 1650, when a subtribe of the Illini Indians moved to the area. When the French, who colonized the region, established a settlement on the Mississippi River in 1699, they named it Cahokia, after this subtribe. A series of disputes between the French and Cahokia Indians prompted French military authorities in 1733 to remove all Indians from the vicinity of Cahokia village and relocate them to the north — where the Mississippian metropolis had once flourished. French missionaries accompanied the Indians, many of whom had converted to Christianity, and established a chapel on the first terrace of Monk’s Mound. Located at the terrace’s southwestern corner, the chapel was only 18 feet by 30 feet. Still, the tiny house of worship marked a milestone in the mound’s history. A sacred site of Native American religion was now under the domain of Christianity. A mound that had been built by Indians was now used by European-Americans.

But tragedy befell this mission community. According to an eyewitness account by a French officer stationed at nearby Fort de Chartres, a band of Sioux, Sauk and Kickapoo attacked the Cahokia Indians on June 6, 1752, killing all they encountered. With so many of its parishioners slain, the mission was abandoned.

Two centuries later, archaeologist Elizabeth Bentley found a small copper hand bell in the grave of a Cahokia-Illini woman who had been buried near the chapel site. It might have been her duty to ring the bell to summon worshipers to Sunday service, and then ring it again during Mass when the priest elevated the host and chalice.

The Cantine Mounds, as Cahokia Mounds was then called, changed hands several times after the mission’s demise. Nicholas Jarrot, a wealthy fur trader who lived in Cahokia village, purchased the site in 1799 for $66. Ten years later, Jarrot sold Cantine Mounds in addition to acreage he owned along Cahokia Creek to some Trappist Monks who had fled France during that nation’s revolution. Dom Urban Guillet, the leader of the monks, founded a new monastery that he named Notre Dame de Bon Secours — Our Lady of Good Help. He planned in time to build a huge monastic cathedral atop the massive mound that had once housed the Mississippians’ leader.

Diseases such as malaria, however, cut down almost half the monks within a few years. Crop failure and a flood further weakened the community. Our Lady of Good Help was severely demoralized by the New Madrid Earthquake of 1812. Dom Urban Guillet was nearly killed by a falling chimney, and the earth beneath the monks’ feet trembled almost daily for two months.

The monks finally gave up and sold the property. After at least two more failed attempts to establish monasteries in the United States, they returned to France following Napoleon’s defeat. But their venture had left behind one enduring legacy — the great mound was now known as Monk’s Mound.

In 1831, Amos Hill built his farm house on the third terrace of Monk’s Mound and utilized the mound for agriculture. A nineteenth- century print depicts the mound thick with corn and orchards. Archaeologists in the 1960s found the remains of Hill’s house and, in the northwest corner of the third terrace, the farmer’s grave.

An 1882 sketch of Monk’s Mound by archaeologist William McAdams also shows trees growing on the terraces, but not in the orderly fashion one would expect to find in an orchard. McAdams prepared and displayed a show called “The Stone Age in Illinois” for the geology and archaeology section of the Illinois Building at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. The show was designed to support McAdams claim that “no other known Stone Age people went further than the Mound Builders of Illinois.” His presentation reached an international audience, and the study of Cahokia Mounds acquired a new importance.

Crowds from the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904 often visited Cahokia Mounds. Photographs taken before and after the fair show that tourists literally denuded the site’s trees by taking leaves for souvenirs. Shortly after the fair, David Bushnell, an archaeologist at the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard, published a scholarly paper about Cahokia Mounds. Bushnell, a St. Louis native, had become interested in the mounds as a youth.

Cahokia Mounds continued to attract attention from scholars and the general public. Unfortunately, it also attracted the attention of the Ku Klux Klan.

The Klan, which had been federally outlawed in 1871, was reborn in 1915 during a rally at Stone Mountain, an imposing granite butte in Georgia. Its campaign against Blacks, Jews, Catholics and immigrants soon found a responsive audience and, by the 1920s, the organization was a force to be reckoned with. Like Stone Mountain, Monk’s Mound towered over the countryside. East St. Louis Klansmen decided that it would be an ideal location for a rally.

On the night of May 26, 1923, a huge cross atop Monk’s Mound was set ablaze to provide a beacon for Klansmen as they journeyed to the rally. Illinois had the fifth-largest Klan membership in the nation, with East St. Louis and St. Louis Klansmen numbering about 5,000. An estimated crowd of 12,000, many of them in full Klan regalia, attended the event, which meant that the Monk’s Mound cross burning drew Klansmen from outside the region. Following the rally, some Klansmen drove through the streets of nearby Collinsville, honking their horns to awaken — and, presumably, intimidate — residents.

The Klan held no more cross burnings at Cahokia Mounds, but such an event underscored the critical importance of protecting the site from further exploitation. In 1925, State Representative Thomas Fekete and State Senator R.E. Duvall, both of East St. Louis, introduced a bill calling for the state to purchase two hundred acres of land around Monk’s Mound. Although only 144.4 acres were actually purchased, it represented a first step toward preserving the site. Cahokia Mounds State Park had been born.

Archaeologists and other scholars were quick to note that 144.4 acres represented only a small portion of the original Mississippian site, which included over 4,000 acres that held 120 mounds. The park has been expanded to 2,200 acres over the years and now encompasses some 68 mounds. A world-class 33,000 square-foot interpretive center opened at the site in 1989.

Mississippian leader’s residence, monastery, fiery cross — the summit of Monk’s Mound has seen it all. Today, for visitors up to the climb, it’s the premier vantage point for surveying the surrounding countryside. The mound is a millennium older than the St. Louis Arch, which was constructed by the culture that eventually superseded these Native Americans. One can only speculate which monument will endure longer.

Bibliography

“Cahokia Mounds Tour Guide.” undated pamphlet published by the Cahokia Mounds Museum.

Carlton, John G. And Allen, William. “A charismatic chieftain — the ‘brother of the sun’ — may have presided over the sudden rise of Cahokia,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch; December 12, 1999.

Chappell, Sally A. Kitt. Cahokia: Mirror of the Cosmos. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Denny, Sidney, Schusky, Ernest and Richardson, John Adkins. The Ancient Splendor of Prehistoric Cahokia. Edwardsville, Illinois, 1992.

Dunphy, John J. “Sunrise at Woodhenge,” Springhouse Magazine (Volume 6, Number 6; December 1989).

— . “A winter dawn at Woodhenge celebrates the sun’s rebirth,” The [Edwardsville, IL] Intelligencer, January 23, 1997.

— . “The Folklore of Monk’s Mound,” Springhouse Magazine (Volume 15, Number 2; April 1998).

— . “The Folklore of Monk’s Mound, Part 2,” Springhouse Magazine (Volume 15, Number 3; June 1998).

— . “Monk’s Mound gives birth to the sun,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 20, 2000.

— . “Cahokia Mounds: America’s Lost Metropolis,” Springhouse Magazine,

(Volume 24, Number 6).

Kimbrough, Mary. “Cahokia Mounds — A City That Time Remembered,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat; February 5–6, 1983

Mink, Claudia Gellman. Cahokia: City of the Sun. Cahokia Mounds Museum Society, 1992.

Henderson, Jane. “ ‘Cool things’ coalesce at Cahokia,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 16, 2009.

Newmark, Judith. “The Wonder At Cahokia,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch; August 3, 1986.

“Woodhenge.” undated pamphlet published by the Cahokia Mounds Museum.

Young, Biloine Whiting and Fowler, Melvin L. Cahokia: The Great Native American Metropolis. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000.

John J. Dunphy’s latest book, Unsung Heroes of the Dachau Trials, includes interviews with veterans of the U.S. Army 7708 War Crimes Group, who apprehended and prosecuted Nazi war criminals after World War II.