A Brief History of Western Military Academy in Upper Alton, Illinois

by

John J. Dunphy

Edward Wyman, a Massachusetts native and 1832 Amherst graduate, moved west and founded the Hillsboro Academy in Hillsboro, Illinois. In 1843, this ambitious educator established the English and Classical High School in St. Louis. After engaging in business pursuits for some years, Wyman returned to education and decided to found a boarding school for young men. While traveling to Hillsboro in search of a suitable location for such an enterprise, Wyman stopped his thirsty steed at a horse trough in Upper Alton and struck up a conversation with a local resident.

When Wyman mentioned the purpose of his journey, the resident suggested that Wyman purchase the old Bostwick Mansion, which was located on Seminary Street in Upper Alton. The mansion, which belonged to nearby Shurtleff College, included some fifty acres of land. Wyman indeed purchased the site and in, 1879, established the Wyman Institute.

Eight years later, Wyman hired Colonel Albert M. Jackson as a teacher and assistant. When Wyman died in 1888, Jackson became superintendent. Wyman’s heirs sold the school in 1892 to Colonel Willis Brown of Buffalo, New York. Brown readily delegated all responsibility for running the school to Jackson and brought in Major George D. Eaton to assist him.

Brown, Jackson and Eaton shared a vision of the kind of school they wanted to lead. The Wyman Institute became Western Military Academy that very year. Jackson and Eaton bought the school from Brown in 1896. Three fires in seven weeks — quite likely the work of arsonists — destroyed Western in 1903, and Jackson and Eaton considered relocating the school to Michigan. The local business community gave its support to the institution, however, and Western was rebuilt. When Jackson died in 1919, Eaton became superintendent and operated the academy for the Jackson family until his death in 1929. Colonel Ralph Jackson, the son of Albert Jackson, became superintendent. His son, Colonel Ralph Borden Jackson, returned from active duty following World War II and began teaching at Western Military Academy. He became assistant superintendent in 1950 and succeeded his father as superintendent in 1955. Jackson held the position until the school closed in 1971.

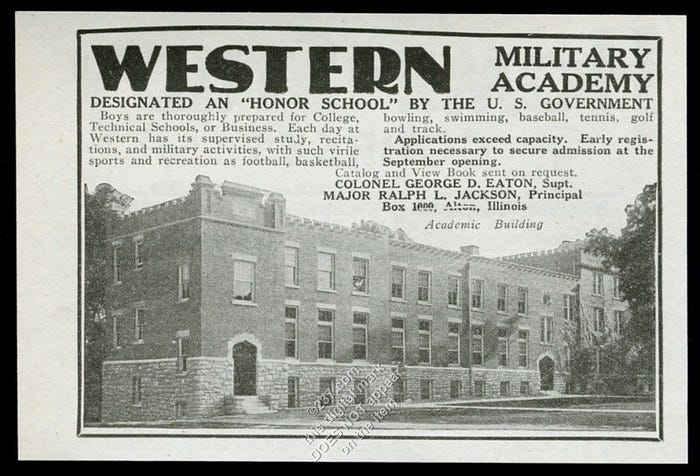

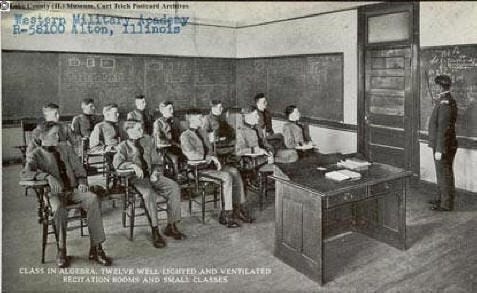

“Western” or “WMA,” as River Bend residents often referred to it, thrived under the Jackson family’s leadership. A 1954 newspaper article noted that the highest rating given to military schools by the U.S. government is the Honor Rating, which is a merit earned by the cadet corps after undergoing a rigid military inspection by United States Army officers. Western Military Academy cadets, the account concluded, had won this top rating continuously since 1926.

Cadets’ uniforms were similar to those worn by cadets at West Point. Spectators at parades viewed adolescents wearing swallow-tail coats with rows of brass buttons and white cross belts. The newspaper reporter observed that Western’s “spit-and-polish” tradition ensured that cadets’ brass buttons and belt buckles shone.

But the cadets’ military training was by no means limited to proper uniform maintenance, the reporter added. The staff included a lieutenant colonel, a captain and four non-commissioned officers who were well-qualified to instruct cadets in use of the standard American weapons of that era. Western Military Academy’s equipment included infantry rifles, machine guns, bazookas, mortars, Browning Automatic Rifles and even a 37-mm cannon.

Napoleon once said that an army travels on its stomach. Fayma Green, Western’s dietician in 1954, told the reporter that “the boys want solid food and plenty of it.” Green claimed that the cadets’ favorite menu for the past seventy-five years was steak or roast beef, potatoes and gravy, green peas and cherry pie a la mode. She also quipped that she could feed five adults on what three cadets ate.

A variety of sports kept the cadets from putting on too much weight from all those calories. Football and baseball were favorites from Western’s earliest days. By mid-century, however, basketball, track, swimming, horseback riding, soccer, golf and boating on the Mississippi all had enthusiasts. Cadets could catch a movie at Upper Alton’s Uptown Theater or enjoy a treat at the soda fountain in Kerr’s Drug Store on College Avenue. St. Louis offered cultural opportunities for cadets wishing to expand their intellectual horizons.

A day began at Western Military Academy in the 1890s with reveille at 6:30 a.m. and ended with taps at 9:15 p.m. By 1954, reveille sounded at 6:15 a.m. with taps at 9:40 p.m. A Western alumnus from the 1960s recalled that, except for Sunday breakfast or during inclement weather, cadets formed companies in front of their barracks and marched to their meals. They remained in formation until they passed through the doors of the mess hall and then proceeded to their assigned seats. The cadets stood at attention behind their seats and sat down on command — but still at attention with their arms extended out and forearms folded. They began eating only when the command was given. When the meal was concluded, they came to attention, rose and were dismissed.

Sunday breakfast was optional for the cadets. This 1960s alumnus recalled that church or Sunday School attendance was required, unless a cadet had a waiver from his parents. This alumnus also noted that he switched denominations while at Western because he preferred attending Sunday School with local girls rather than a two-mile march to church!

Its successful combination of academic excellence and military training extended the academy’s reputation beyond the River Bend and greater St. Louis area. Many of its students over the years included young men from Mexico as well as Central and South American nations.

Western Military Academy produced leaders, a fact exemplified by its distinguished alumni. General Paul Tibbets, who piloted the airplane Enola Gay that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan on August 6, 1945, graduated from Western in 1933. Tibbets returned to Alton in 2000, when Western alumni held a reunion in St. Louis.

Sandy Vanocur, class of 1946, also returned to Alton during that reunion. Vanocur recalled an instructor in Latin and German at Western recommending that he use his voice in his chosen career. Vanocur took the advice and became the vice-president of ABC-TV news. In 1960, Vanocur moderated the televised debate between presidential candidates Richard Nixon and John Kennedy.

One particularly distinguished Western alumnus was absent from that 2000 reunion — Edward (Butch) O’Hare, class of 1932, who was killed during World War II. O’Hare, who went on to graduate from Annapolis and became a pilot, won the Congressional Medal of Honor for saving his aircraft carrier, the Lexington, in 1942 by single-handedly shooting down five Japanese planes. He went missing in action after a 1943 mission and was declared dead a year later.

Other Western graduates who chose military careers include Major General W.P.T Hill, class of 1914, who served as the Marines’ quartermaster general during World War II, and Major General Harry Collins, class of 1915, the commander of the Rainbow Division during that war.

But a military career wasn’t the only option for a graduate who wanted to make a name for himself. Thomas Hart Benton, class of 1906, became an internationally-acclaimed painter, while William S. Paley, class of 1918, rose to chairman of CBS. Hari Van Hoeffer, class of 1925, embarked upon a successful career as an architect in St. Louis.

Nearly 4,000 cadets graduated from Western during its 92 years of existence. Over 500 of those young men served in World War I, while double that number served in World War II. Forty Western graduates gave their lives in that latter war.

It is uncertain how many Western graduates saw action in the Korean and Vietnam conflicts. Robert Ellison, class of 1963, chose photojournalism rather than the military but nonetheless died in the Vietnam War. The C-123 plane he had boarded with 48 Marines was hit by enemy fire while attempting to land. Ellison’s photos of Marines during the siege of Khe Sanh were published in Newsweek after his death at age 23.

As an all-boys’ school, it was inevitable that Western would develop a special relationship with Monticello College. “Monti girls” served as cheerleaders for Western’s teams at sporting events. They were also frequent guests at dances held at the academy. Western alumnus Chuck Forsberg joked that so many phone calls were made to Monticello College from the academy that the local exchange switch sometimes stuck on the Monticello exchange!

Western offered avenues of expression for the creative outlets of its students. There were military and concert bands, a glee club and even a jazz orchestra. Aspiring authors could write articles for Shrapnel, the student newspaper, and Recall, the yearbook. Boys with a taste for electronic journalism became involved with WMAS, Western’s experimental radio station. Broadcasting on both the AM and FM bands, WMAS hit the airwaves in the late 1950s and featured sports, comedy, music and whatever else struck the fancy of its staff.

While appealing primarily to the Western Military Academy student body — and, perhaps, the young ladies of Monticello as well — WMAS garnered no small amount of community support in Upper Alton. The Thrifty Drug Store provided records for air play, while businesses such as the De Luxe Café, Uptown Theater and Alton Hardware and Paint Company bought advertising.

Western Military Academy entered the 1960s with every hope of educating new generations of American and Latin American boys. However, WMA graduated its last class in 1971. Declining enrollment forced the school to close its doors forever.

Much like Monticello College in nearby Godfrey, Illinois, which also graduated its final class in 1971, Western Military Academy fell victim to a changing nation. By the end of the 1960s, all-women’s colleges such as Monticello were no longer popular. Military academies also had lost much of their traditional appeal. The Vietnam War — America’s longest and most unpopular conflict — had polarized the nation and had cast the military in a negative light. Uniformed personnel routinely were subjected to public scorn. In 1969, just two years before closing, Western Military Academy ended its long-standing tradition of requiring cadets to wear their uniforms when traveling home during vacation because these young men were now subjected to taunts and insults. In such a political atmosphere, it is hardly surprising that enrollment plummeted at Western and other American military academies. WMA became a homefront casualty of the Vietnam War.

Colonel Ralph Borden Jackson, Western’s last principal, and his family continued to live in the school’s C Barracks. Jackson, who now supplemented his income as a substitute history teacher at Alton High School, attempted to maintain the buildings and grounds, but vandalism began taking a heavy toll. A stained-glass window in the school’s chapel that depicted St. George and the Dragon was smashed. Copper tubing was stripped from the bathrooms and indoor swimming pool. Desks were ransacked and library bookcases overturned.

Western Military Academy was reborn as an educational institution in 1978 when the site was purchased by Faith Community Church, a Godfrey, Illinois congregation, for use as a Christian school. While extensive renovation was necessary as well as demolition of some decrepit buildings, Mississippi Valley Christian School now thrives at the location.

Final taps may have sounded for Western Military Academy, but its legacy lingers. The school’s graduates have networked to share memories and, even decades after its closing, an alumnus occasionally visits Alton just to see the old campus.

Bibliography:

“It began at a horse trough,” The [Alton, IL] Telegraph; June 4, 1971.

Heine, James. “WMA Ends In Fourth Generation,” The Wood River [IL] Journal; July 13, 1977.

Scott, Robert H. Jr. History of Western Military Academy, Alton, Illinois, 1879–1971. 2006.

Start, Clarissa. “Western Military’s First 75 Years,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch; May 27, 1954.

Thomason, Arthur J. “He strains to keep his heirloom able to pass muster,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat; September 27, 1975.

— . “Last Reveille to sound soon for colonel at closed school,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat; February 3, 1978.

Waley, Dave. “Tibbets stars at reunion,” The [Alton, IL] Telegraph; August 27, 2000.

http://omen.com/wmapix.html; accessed 1/6/07.

http://omen.com/rfm.html; accessed 1/6/07.

- John J. Dunphy’s latest book is “Unsung Heroes of the Dachau Trials,” which includes interviews with veterans of the U.S. Army’s 7708 War Crimes Group.